Picture the scene: A shepherd visiting a remote area stumbles upon strange wreckage strewn across the ground which could be the remains of a crashed spaceship. The debris consists of pieces of unusual metal and strange drawings. On reporting his find at the local police station, search teams and military personnel descend on the area. The wreckage disappears – no one knows where – and civilians are told to ‘keep quiet about it.’

You are probably thinking ‘Roswell, New Mexico, 1947’.

But no, this incident occurred in the Scottish Highlands one spring morning in 1962. It has uncanny links to its American cousin, even down to the ‘cover story’ used hide the true identity and purpose of the ‘crashed spaceship.’

In the Scottish case the shepherd, Donald MacKenzie, reported the debris ‘looked like a Sputnik’. In the early ’60s all Soviet spacecraft were subject of intense interest in the West at that time. The debris found by William ‘Mac’ Brazel in the New Mexico desert was also found at a fortuitous moment in Cold War history: during the summer of 1947 no one could pick up a newspaper in North America without seeing a mention of ‘flying saucers.’

The Soviet satellite Sputnik, first launched in 1957, was the first man-made satellite to orbit the Earth (credit: jpl.nasa.gov)

When Brazel reported his find to the local sheriff, intelligence officers from the Roswell Army Air Base came out and collected it. A hasty press release announced the air force had captured one of the ‘flying saucers’. But what appeared to be a quick resolution of the mystery was soon deflated by an official statement that the debris was actually from a lowly weather balloon. This was too good a story to die. Some of those who had seen and handled the wreckage were not convinced. And the seeds of a modern legend had been sown.

In the Scottish case the shepherd’s story was initially greeted with a deal of speculation, probably based upon the quality of the local malt whisky. It was three months before a team from RAF Kinloss reached the crash site near Ardgay in Easter Ross. By now it was October 1962 and the world was collectively holding its breath as the Cuban missile crisis played itself out on the international stage. The Cold War was at its most dangerous phase.

What the team found on the remote moor was a strange box-shaped object, large enough to have carried a person, but with no signs of damage caused by the intense heat that would have been expected if this really was a satellite. The structure contained spaces for cameras and a brass panel that explained, in pictures, what the finder should do in the event of discovery to claim a reward. Buried nearby were ‘a number of bottles of colourless fluid’. Had someone reached the scene and removed items from the crash site? The ambiguity left some members of the team convinced this was indeed part of a crashed Soviet spacecraft and some believed that until the end of their lives. But if so why was it in such a good condition? And where was the parachute?

As Frank Card’s history of the RAF Mountain Rescue Service (Whensoever, Ernest Press 1993) points out, like all good legends this ‘was an event that, by its nature, has remained unknown, except to the privileged few ever since.’ And when the team’s report found its way to Squadron Leader John Sims at RAF Kinloss he made inquiries with the Air Ministry. He was told he had ‘no need to know.’ All mention of the incident was excised from the base and team records. Shades of Roswell yet again. What was it about the crashed object that required a security crackdown under the Official Secrets Act?

Secrecy breeds speculation and the crackdown on questions simply encouraged rumours to spread and others to pass on stories they have heard to others. Today the legend is firmly established in the folklore of the region. In July 2012 it resurfaced again in a BBC News Online story that claimed ‘a former RAF Kinloss Mountain Rescue Team leader has told how he sought evidence that a Russian satellite crashed in the Highlands 50 years ago.’ According to this version, former Kinloss Mountain Rescue Team leader David ‘Heavy’ Whalley was so fascinated by the rumours that he made his own inquiries into the team’s records, but could find no mention of the discovery in the logbooks. But a colleague, Jack Baines, was part of the team that visited the crash site. ‘They found various bits and pieces,’ Whalley recalled.

‘Jack said the team were told to keep quiet about what they had found. When he told me the story I first thought it was an urban myth, but he convinced me and I believe they definitely found a crashed Sputnik.’

And this is the point where the uncanny links between the Ardgay and Roswell incident come into sharp focus. For aviation historian Keith Bryers is convinced the debris found in Scotland was not a spacecraft at all. It was in fact the payload of an American spy balloon similar to the Mogul balloons which the USAF later admitted was the source of the original Roswell incident.

The evidence he has collected is convincing and consistent with information I found in British government files released at The National Archives. Years before the first satellites, the USAF used Scotland as a base for launching enormous camera-carrying balloons designed to spy on the Soviet Union. The UK base for the balloon project – code-named ‘Moby Dick’ or Project 119L – was the Royal Navy airbase at Evanton. For a period in 1955-56, dozens of balloons were launched from the base near Inverness, on a mission to ride the jet stream to the Soviet Union where cameras attached to the glassfibre gondolas took photographs of military and nuclear facilities on the ground.

A 1956 file marked ‘Top Secret- USAF Meteorological Experiments’ describes the gondolas as box-shaped and weighing 400 ibs and painted bright yellow. It adds: ‘Recovered gondolas are to be treated as ‘classified’ equipment and under no circumstances is a gondola to be opened.’ A press release in a file listing ‘cover stories’ dated 9 January 1956 adds:

‘Large plastic balloons, which have often been mistaken for “flying saucers” will carry meteorological instructions, including cameras to photograph clouds and radio equipment to record atmospheric information.’

These balloons were enormous – up to 176 ft in height and 128ft wide (the height of a 20 storey building) and the USAF believed they could evade the Soviet MiG fighters by rising to 55,000 ft. Once clear of Soviet territory the gondolas were designed to drop into the Pacific Ocean where VHF beacons would guide recovery squadrons to the precious payload.

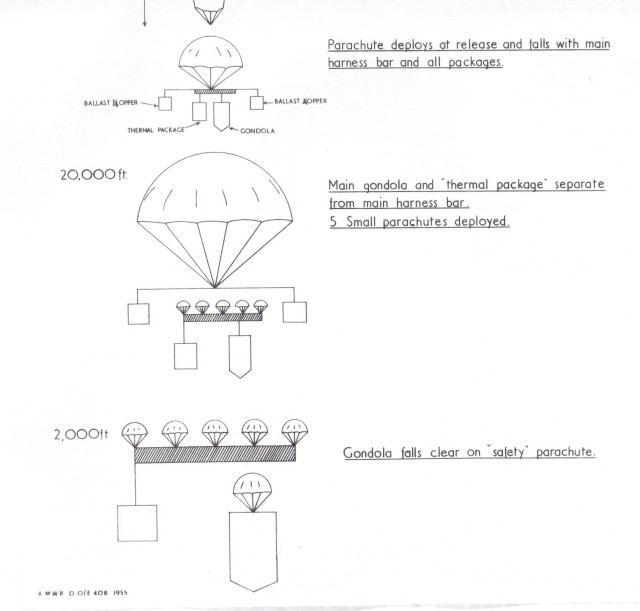

Extract from Top Secret RAF document ‘showing sequence of events following electronic triggering of balloon release mechanism’, showing main gondola attached to Project 119L spy balloons (TNA AIR 2/17904)

According to files on the project opened at The National Archives in 1998, the Pentagon spent $68 million on the balloon programme and created an elaborate smokescreen to conceal their true purpose. If the balloons were shot down or captured by the Soviet Union the official line was that they were ‘part of an Air Force meteorological survey of the northern hemisphere’, in effect ‘weather balloons’, much the same cover as was used at Roswell. Bogus press releases were written and only the most senior USAF and RAF officials were told what the operation was really about.

Ironically, despite the massive investment, the balloon project was a dismal failure for the West. Soviet fighters shot down many of the balloons and 50 were put on display in Moscow. And by March 1956 when the project was terminated, a more effective method of aerial reconnaissance – the manned U-2 spyplane – had begun operational flights. Of the 448 balloons released in total, just 40 gondolas were successfully retrieved – just one of these originated from Scotland. The final word goes to Keith Bryers, who says he believes the device found by Donald MacKenzie was probably the remains of a Moby Dick balloon that had ‘blown off course shortly after launch and that US personnel simply removed the most sensitive items thus avoiding the effort of recovering the whole device probably in foul weather.’

Six years passed before the shepherd discovered his Sputnik and triggered off a modern legend: Scotland’s answer to the Roswell incident.

Great stuff!