On 13 August 1956, with the Suez crisis approaching and the Soviet threat at its height, the RAF launched waves of aircraft to intercept unidentified flying objects which penetrated the UK’s radar shield and were circling a nuclear-armed American airbase in Suffolk.

Although dozens of aircrew, both British and American, played a role in these events the full details of the case were kept secret for decades. The British Government have never offered an explanation for the incident, which was listed as “unexplained” in a Secret briefing to Ministers in 1957.

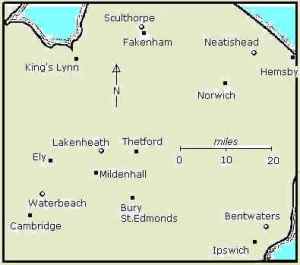

These events took place around the airbase at Lakenheath and Bentwaters in Suffolk that was in 1956 loaned to the United States Air Force by the RAF. Over the years the case has achieved an iconic status in UFOlogy second only to the famous Rendlesham Forest incident of 1980 which also occurred in East Anglia and involved US airmen.

But the 1956 incident was the only UK case listed as “unexplained” by the Colorado University study of UFOs commissioned by the US Air Force in 1969. And its high degree of “strangeness” helped to convince a number of scientists, including astronomer Dr J. Allen Hynek, that UFOs deserved serious study.

At face value, this is one of the few UFO cases that appears to provide the type of “solid” evidence demanded by sceptics. Perhaps uniquely, it involves phenomena that were detected by a number of independent military radars over a lengthy period of time, both from the ground and from the air. What’s more, this evidence is supported by testimony from a number of credible witnesses including senior military officers, aircrew and radar personnel. As radar expert Gordon Thayer, of Colorado project, commented:

“…the apparently rational, intelligent behaviour of the UFO suggests a mechanical device of unknown origin as the most probable explanation of this sighting.”

In 1956 the Cold War was at its frostiest and all military secrets were closely guarded. At the time the British public were told nothing about the events that unfolded in the night skies above East Anglia.

Even today the airfield at Lakenheath remains one of the most sensitive American bases in western Europe. And despite the dismantling of the Iron Curtain the USAF continue to store over one hundred nuclear weapons there. In July 1956 – just weeks before the UFO alert took place – a USAF B-47 crashed into a storage silo containing three Mark 6 nuclear bombs (the type used to destroyed Nagasaki), exploding and spreading burning fuel over the bombs. Experts said it was a miracle that exposed detonators on one bomb did not fire, as this would have spread nuclear material across the East Anglian countryside.

This near catastrophe was kept secret for two decades until it was leaked by a retired USAF general. Such tight security was deemed necessary because the base was home not only for nukes but was also used as a forward base for the CIA’s U2 spyplane, which flew from Lakenheath in the summer of 1956 at the time of the UFO incident. The U2 was initially so secret that it was shipped into the base in banana boxes and was heavily guarded.

Everywhere, nerves were jittery and war was expected to break out at any minute. In August tension was growing as Britain and France were about to become embroiled in the Suez crisis following Nasser’s nationalisation of the Suez canal. In the east, the Soviets were crushing the rebellion in Hungary and a nuclear confrontation appeared just months away.

Seen from the perspective of hindsight it is understandable that the authorities should decide to say nothing about a troubling incident which highlighted the limitations of their air defences. Any information released could, from their point of view, be helpful to the enemy.

By 1968, when Forrest Perkins sent his account to the Colorado University team, there was less secrecy and civilians were able to gain access to classified USAF records on the case held by Project Blue Book. But with time running out to complete their project, they were not able to question the RAF pilots or obtain an account of the case from the British MoD. And when the case was finally made public in 1969, it emerged that vital records of the Air Ministry investigation had already been destroyed in a clear out of old papers.

The loss of the British files has meant those who tried to investigate this mysterious incident have had to rely upon a confusing and contradictory version of events largely written from the American perspective. But slowly, in more recent years, as aircrew and the RAF fighter controller who controlled the interception came forward or were traced, some of the many pieces of this historical jigsaw puzzle have been fitted into place.

Since 2000 a team of researchers who are interested in UFOs and Cold War history have re-examined the fine detail of this classic case. By using investigative techniques we have gained access to documentary evidence including documents formerly with-held by the USAF, RAF and MoD. In addition, we have traced dozens of participants and witnesses, and unearthed hundreds of pages of documentary evidence.

The testimony we have unearthed has demonstrated that the “classic” case familiar to UFOlogists was actually a serious air defence crisis at the height of the Cold War, which has remained secret for half a century.

The ‘UFO’ incident recalled by Forrest Perkins turns out to be just one small part of a complicated series of interlinked incidents spread over a period of up to ten hours which contributed to a major air defence alert.

Reconstruction

After years of research and debate here is what I believe to be the most complete reconstruction of the Lakenheath incident that is possible from the surviving evidence:

The evening of Monday, 13 August 1956 was clear and calm in Eastern England. As the day ended there was nothing to indicate this would become one of the most spectacular encounters between UFOs and the military in the 20th century.

At 9.30 pm a USAF radar unit at RAF Bentwaters, near Ipswich, tracked a UFO on radar 25 to 30 miles east of the base. When it disappeared to the northwest at 4,000 mph it quickly became apparent this was no ordinary aircraft. Elsewhere a second airman was watching two formations of slow-moving ‘blips’.

At this point the RAF scrambled a Venom fighter from the airfield at RAF Waterbeach, near Cambridge. But shortly after take-off the aircraft lost one of its wing fuel tanks which crashed into a field on the outskirts of the city, fortunately without causing injury. The Venom was forced turn back, so two USAF T-33 jets on a training exercise were sent to search for the UFOs which were still visible on radar at RAF Bentwaters. They found nothing, but one of the pilots, Chuck Metz, speaking in 2002, told us that he was convinced they were caused by “strange weather conditions” (read Metz’s full account here).

But shortly after this flap had subsided, another UFO moving at hypersonic speed zoomed across the radar scopes. Seconds later airmen in control tower saw “a bright light” zip overhead at terrific speed, but no sound was apparently heard. A pilot in a C-47 transport aircraft also reported sighting this blurry light apparently beneath his aircraft “traveling east to west at terrific speed.”

Sometime after these events Bentwaters called Lakenheath and asked the USAF base to keep a look out for anything unusual. The air traffic supervisor, Forrest Perkins, asked his controllers to check their screens and within a short time they detected “targets” on their scopes to the southwest. The targets stopped and started in an unusual fashion and moved in a northerly direction at speeds of 400-600 mph. Similar echoes were spotted in the same direction by a second radar at the base which used a different frequency.

At this point Perkins decided it was time to take his concerns to the top brass. He alerted the USAF and, through them, RAF Fighter Command who were responsible for air defence of the UK. Around midnight the senior officer at Neatishead on the Norfolk Broads, Flt Lt Freddie Wimbledon, checked his screens and was amazed to see something on his radar at 10-20,000 feet over the UK that behaved unlike anything he had seen before. Something “that travelled at tremendous speeds and then stopped.” Alarmed, he immediately set up an interception team crewed by four, and ordered another four airmen to monitor the action.

Meanwhile Fighter Command called for a Venom night fighter to launch from the “Battle Flight” who were on 24-hour alert at RAF Waterbeach. They knew that a senior officer, Squadron Leader Anthony Davis – who had WW2 combat experience – was already airborne flying a Venom from his alert squadron, No 23. Davis was ordered to divert towards Lakenheath to investigate.

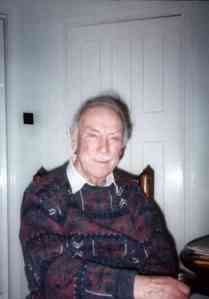

Freddie Wimbledon describes what happened next:

“After being vectored onto the tail of the object by the Interception Controller the pilot called ‘Contact’ then a short time later ‘Judy’ which meant the navigator had it fairly and squarely on his own radar screen and needed no further help from my controller. After a few seconds, in the space of one sweep of our screens, the object appeared behind our own fighter and our pilot called ‘Lost contact, more help.’ He was told the target was now behind him and I scrambled a second Venom which was vectored towards the area.”

One of the Venoms described by Wimbledon appears to have been piloted by Wing Commander (later Air Commodore) Anthony Davis DSO DFC, who died in 1988. He was a WW2 fighter pilot whose later career included a spell as Air Attache to Moscow (1963-66). Ironically, after retirement from active service in 1968 Davis was retained by MoD and in 1971 became head of the civilian MoD secretariat, S4 (Air), that was responsible for the analysis of UFO reports!

Davis’s own brief written account of his involvement in the Bentwaters-Lakenheath incident, which I discovered in MoD papers during 2003, reveals that he was already airborne in a Venom interceptor from RAF Coltishall when the UFOs were detected. He was vectored by GCI radar (presumably by Wimbledon at Neatishead) towards “a suspected UFO” but his radar operator could not make contact with it and Davis found himself “chasing a star.” This star may have been a bright planet, either Mars or Venus, both of which were prominent in the clear night sky.

(Responding to a question from a member of the public in 1972 Davis said Air Ministry papers on the incident had been destroyed “…but if there had been any evidence to indicate the existence of an unidentified but real flying object (and not just an anomalous radar echo) [they] would of course have been retained and investigated in great depth.”)

For his part, Freddie Wimbledon remembers the blip had “disappeared” before the second Venom was able carry out an interception. He said: “…it appeared to ‘give up the chase’ as though it had achieved its objective and more or less ‘melted’”. While this might suggest the UFO was not a solid object, he remains adamant the UFO echo was strong and clear. He said it was similar in size to a fighter aircraft but capable of “terrific acceleration and apparently stopping without slowing down,” behaviour impossible for any known aircraft in 1956 or indeed today.

This drama was simultaneously overheard by two other groups of witnesses thousands of feet below on the ground. These included Forrest Perkin’s USAF team at Lakenheath who were listening to the transmissions and airmen from the RAF’s 23 Squadron who were waiting for orders in the crew room at Waterbeach. During the action after midnight, a crowd had gathered around a radio receiver tuned to the frequency the interceptors were using. Airman Graham Schofield, who told his story for the first time, said:

“We could hear the various voices and recognised the distinctive voices of the individuals. The first crew made radar contact and closed rapidly on to the target…they tracked it down to within about three miles and then lost contact. They were called off and the second crew instructed to make an intercept. They also reported radar contact at about ten miles directly ahead. The navigator called off the distance as the target rapidly closed. At one mile there was a shout of confusion from the pilot who had seen nothing. We then heard ‘I think they are now on our tail!’.”

And this amazing sequence was not the end of the excitement. Lakenheath’s radars continued to spot UFOs into the early hours of 14 August 1956. Later in the night more UFOs appeared on Lakenheath’s radars and fresh orders led the RAF to scramble yet another wave of Venoms from RAF Waterbeach to intercept them. New light was thrown on these events in 1995 when our team interviewed two members of 23 squadron who took part in the second phase.

Navigators John Brady and Ivan Logan – who operated the Venom’s radar – along with their pilots Dave Chambers and Ian Frazer-Kerr, recalled the incident because in all their years service it was the only occasion they had been ordered to intercept a target at such low altitude overland. Their impression was that if an enemy aircraft had penetrated the UK’s radar shield to reach the mainland it was already too late.

Brady manned the radar in one Venom scrambled at 2 A.M. and once airborne the men were asked to contact the USAF at Lakenheath who would direct them towards the UFO. By this stage the “target” could not be detected by RAF Neatishead because it was below its radar horizon. Brady explains what happened next:

“The USAF were directing us towards this thing at around 7,000 feet. The first run we had at it I saw nothing. The next time we turned onto a reciprocal heading and I then obtained a contact which I held 10-15 degrees off dead ahead and noticed that it raced down the tube at high speed. We were flying at around 350-400 mph. I remember saying to David: “CONTACT…there, it’s out 45 starboard now at one mile’… and he kept saying to me “Where is it? Where is it? I can’t see it!” as we rushed past. And it would go down the right hand side or the left hand side. Two further runs were made with the same result and it was fairly obvious that whatever it was, it was stationary. Dave looked out on each run but could see nothing. My radar contact was firm but messy but there WAS something there.”

Before returning to base they were told that a second Venom was on its way to the scene. But Ivan Logan and Ian Frazer-Ker had no more success. “I recall picking up a contact several times usually at about three or four miles,” Logan told us. “As it appeared to be virtually stationary we could not turn behind it. Our targets [aircraft] were normally travelling at our speed and when in behind we synchronised speeds at visual range. In this case it was impossible.”

Logan gave up and returned to Waterbeach after 3 A.M. on the morning. Shortly afterwards the mysterious stationary blip had melted from the radar screens at Lakenheath and did not return. Coincidently, this disappearance coincided with a change in the weather, with clouds now covering what had been a clear summer sky.

Speaking in 2002, Brady was keen to point out that although he remembered using the word ‘contact’ “never at any stage was there a visual sighting, since there was nothing to be seen.”

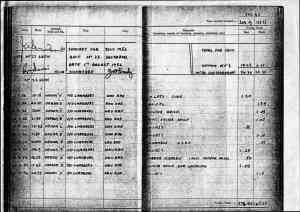

Brady described the radar target as “a little, faint paint…you wouldn’t call it a real, positive blip – it was ephemeral.” The two men decided the “blip” they saw was probably a meteorological balloon because that was the only explanation that made sense. This was in fact the same conclusion entered in the 23 Squadron Diary, discovered in 2001, which simply states:

“…two aircraft were scrambled after a strange object had been picked up by Lakenheath GCA [Ground Controlled Approach radar]. The GCA became a GCI [interception] and several attempts were made to intercept the ‘object’, but as it was standing [still] it was most difficult and nothing was seen by either of the crews, and it was later decided that the object must have been a balloon.”

For their part, in 2001-2 both Brady and Logan recalled:

“I don’t think any of us heard about other aspects of the incident until 40 years later. Although we all thought it was unusual none of us connected it with UFOs or alien visitors.”

Nevertheless, at the time it appears the Lakenheath incidents set alarm bells ringing both in London and across the Atlantic.

Shortly after the USAF reports were filed a “Secret” cable was sent from the US Air Force Headquarters in Washington warning of “considerable interest and concern” at the sightings and demanding an immediate inquiry. The cable asked if the sightings were linked to a similar scare reported by a British radar station on the Danish island of the Bornholm in the Baltic a week earlier. In this case, there were fears that the UFOs were in fact guided missiles launched by the Soviets.

What the British Government made of the Lakenheath incident remains a mystery. They maintain that all papers on UFO incidents before 1962 were routinely destroyed many years ago, so they are unable to comment.

But the late Ralph Noyes, who served as a senior official with the Air Ministry at the time of the incident, and who retired at the grade of Under Secretary of State, told us in 1988:

“Here we had a number of object seen coming in across the North Sea on coastal radar. It looked like a Russian mistake. Jet aircraft were scrambled. The objects were travelling at quie impossible speeds like 4-5000 mph and then came to an abrupt halt near to one of these stations not very high up. Jet aircraft picked them up on aircraft radar. The objects then simply made rings round them…Inevitably this led to the sort of enquiry which you would put in hand if you had any military responsibilities. Had something gone wrong with ground radar or with aircraft radar? We experienced pilots going out of their minds? Were people having fantasies? We *had* to investigate cases of that kind. Over the years – although there were not an enormous number of such cases – there were a sufficient number to persuade me, and a number of air staff friends with whom I had to work, that something was going on, sporadically, in British airspace which we could not explain. But we did not particularly want to make public statements about that. Not for something that we had no explanation.”

Copyright David Clarke 2011

(for details of a second UFO interception incident involving USAF F-86D aircraft that occurred in UK airspace during 1956/57 read my feature article, ‘Intercept and Destroy‘).

Dr Clarke,

Thanks very much for this. I always appreciate how you look thoroughly at the evidence and point out the unanswered questions and mysteries without leaping to unwarranted conclusions. Great work!

Sincerely,

David R.

Thank you for all the trouble

Thanks 🙏

Fantastic article as always. Thanks David!